The limits of regulation

In this blogpost, we will discuss how regulations, such as protection laws, environmental policies, and financial restrictions, can be understood through a systems science perspective.

As a starting point, I want to submit a rather systems-sciency statement: "Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system" [1]. This was the title of a highly cited paper written back in 1970.

While it may sound a bit dull at first, there is some universal truth to this proposition. Whether you have a background in law, politics, economics, biology, or physics, effective regulation is impossible without an accurate model of the system you want to regulate. Even if that model exists only implicitly in your head. Without such a model, any regulatory action becomes little more than blind guesswork.

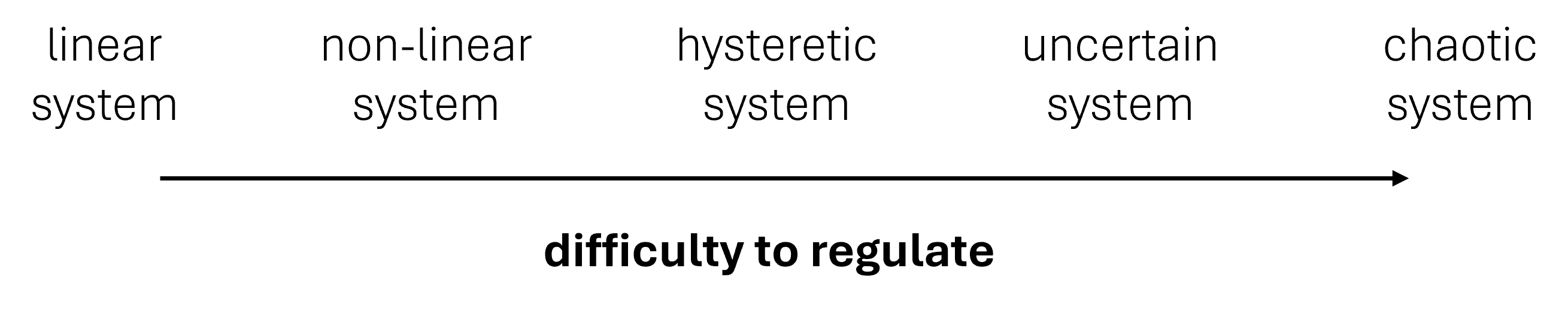

In the following, we will look at regulation through examples from various fields, moving from linear to nonlinear and ultimately to chaotic regulation. Along the way, we will see that even with accurate models at hand, there are limits to what regulation can achieve.

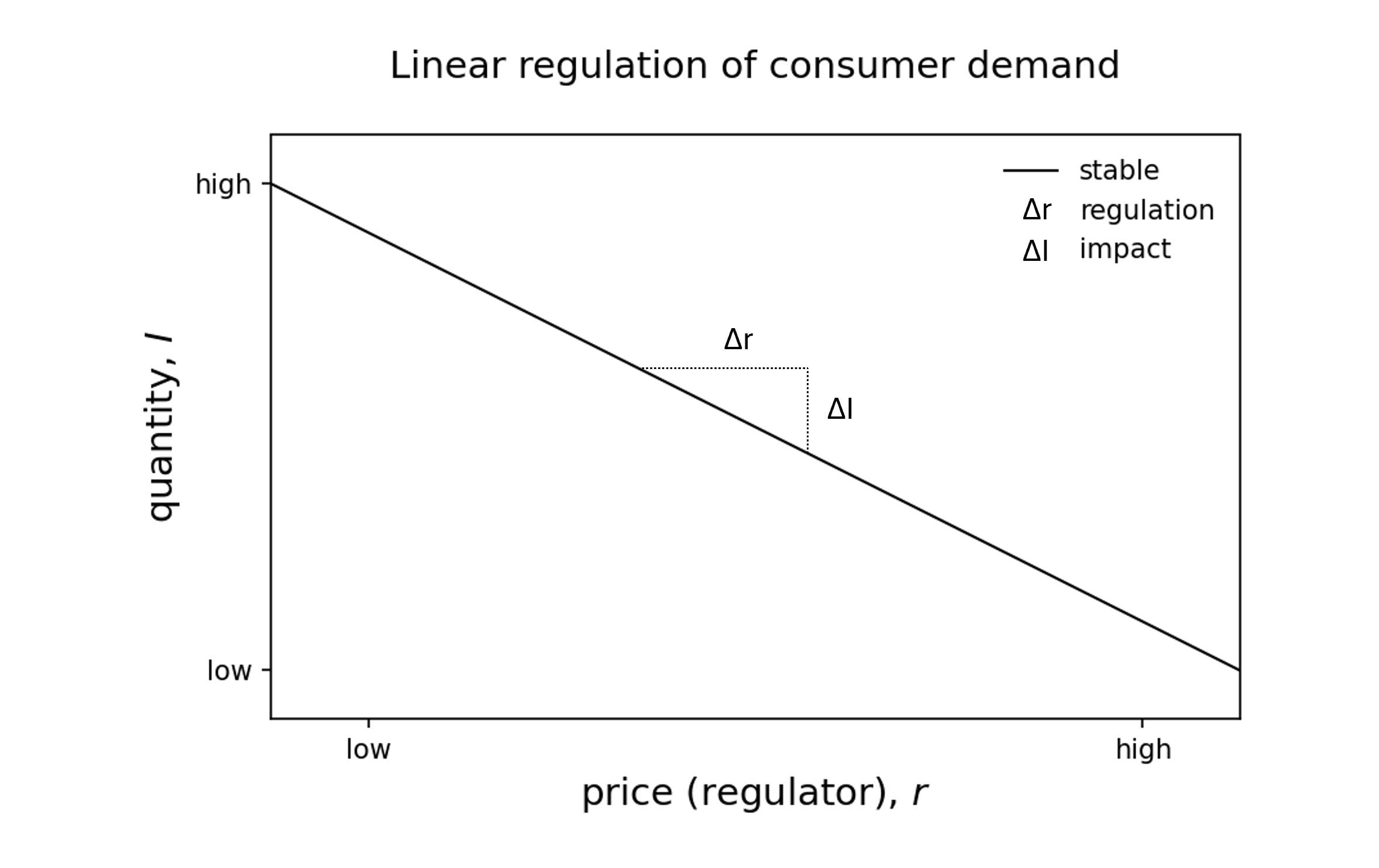

Linear regulation of consumer demand

In a simple linear system, regulation is straightforward. For example, increasing the price of a product (regulation, Δr) means that consumers will buy less of that product (impact, ΔI). Because we have a linear demand, the relationship between regulation and impact is the same anywhere on that demand function.

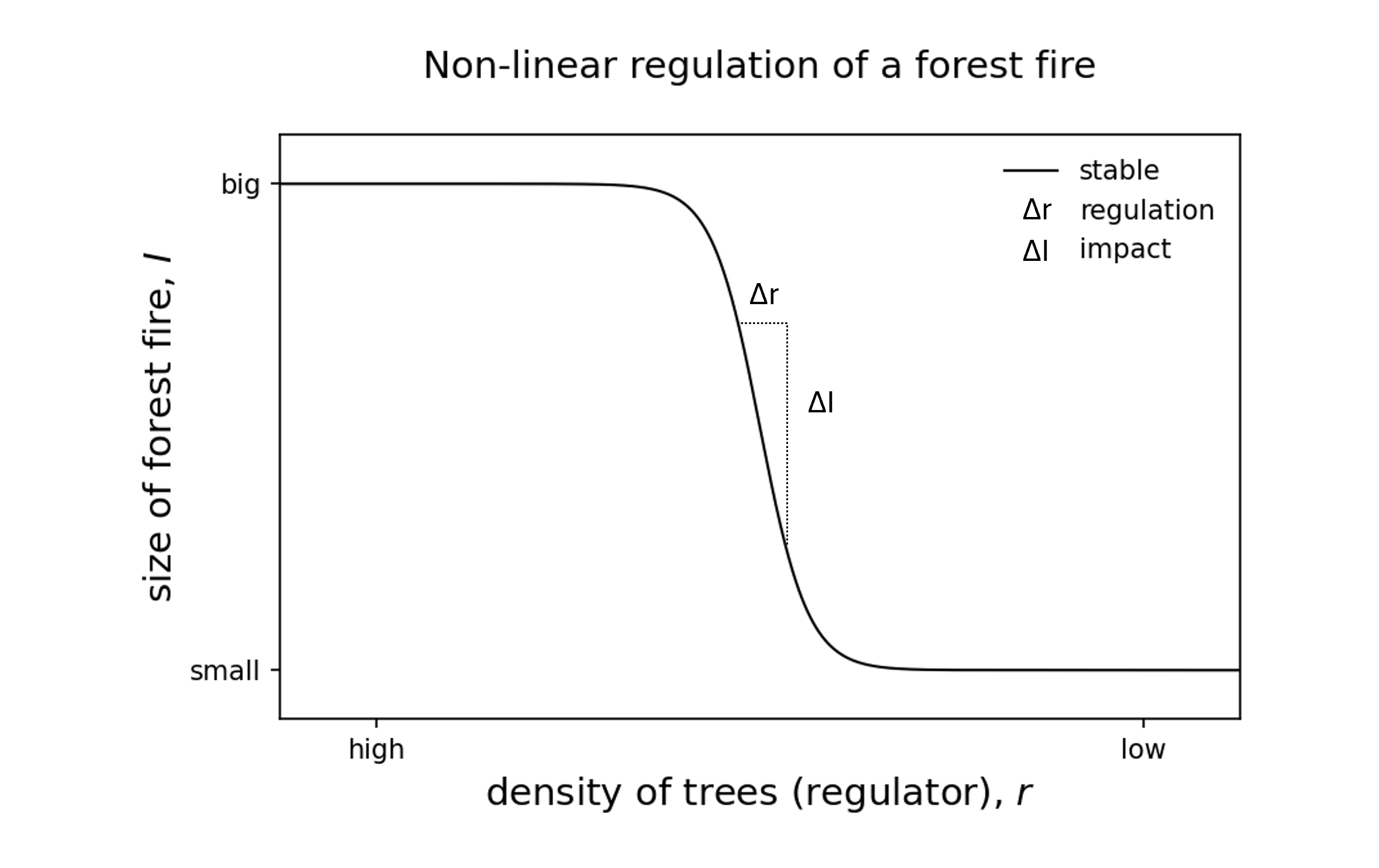

Non-linear regulation of forest fires

Not all systems respond linearly to regulation. Take a dense, overgrown forest: initially, reducing tree density may have little to no effect on the area burned in a wildfire. However, once a certain threshold is crossed (regulation, Δr), where trees are spaced far enough apart that fire struggles to spread, the fire size drops dramatically (impact, ΔI). In such a non-linear system, regulation has virtually no impact over a wide range of conditions until, suddenly, it has an enormous effect.

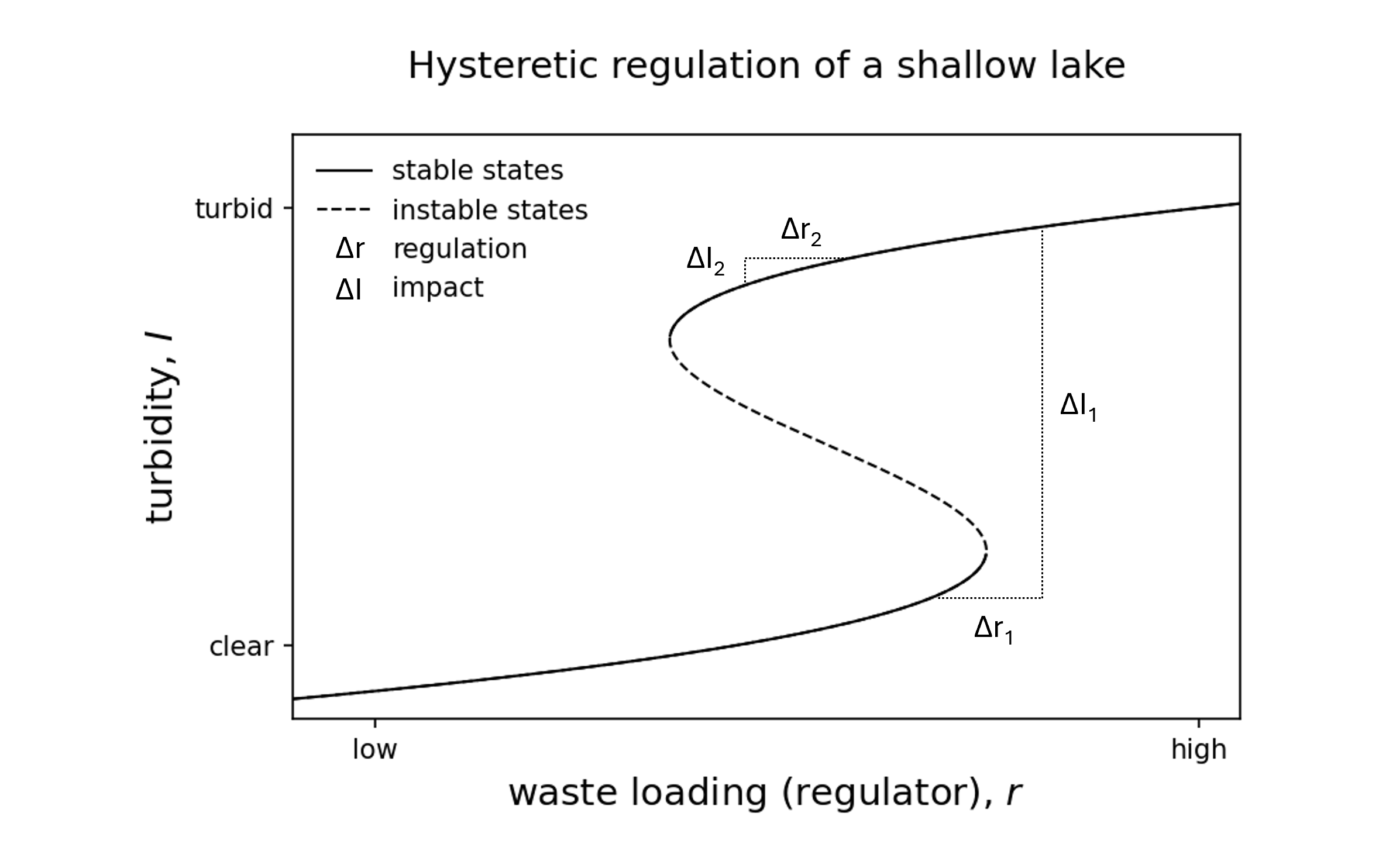

Hysteretic regulation of shallow lakes

Some systems can even resist back-regulation. Take a clear and healthy shallow lake: increasing waste loading (regulation, Δr1) can abruptly push it into a turbid and algae-dominated state (impact, ΔI1). However, once the lake has tipped, simply reducing waste (back-regulation, Δr2) will not immediately restore it to its clear state (impact, Δr2). Instead, the system demands significantly stronger corrective action to overcome the hysteretic effect, making reversal far more challenging than the initial shift.

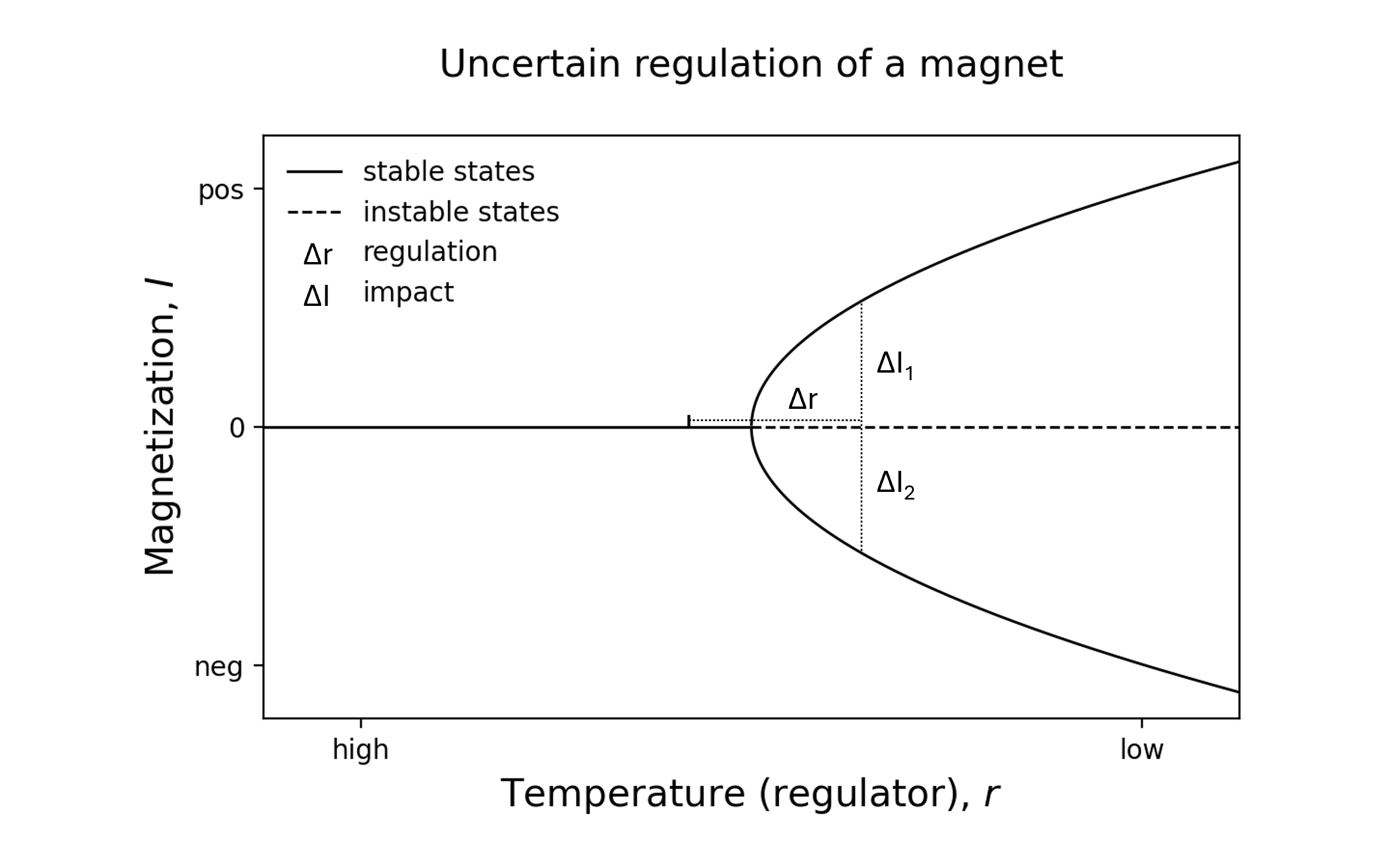

Uncertain regulation of magnets

Some systems introduce uncertainty in their response. For example, in magnets, changing the temperature (regulation, Δr) past a critical point leads to a pitchfork bifurcation, where magnetization can flip to either a positive (impact, ΔI1) or negative (impact, ΔI2) state. Here, regulation works, but the direction of the impact becomes unpredictable.

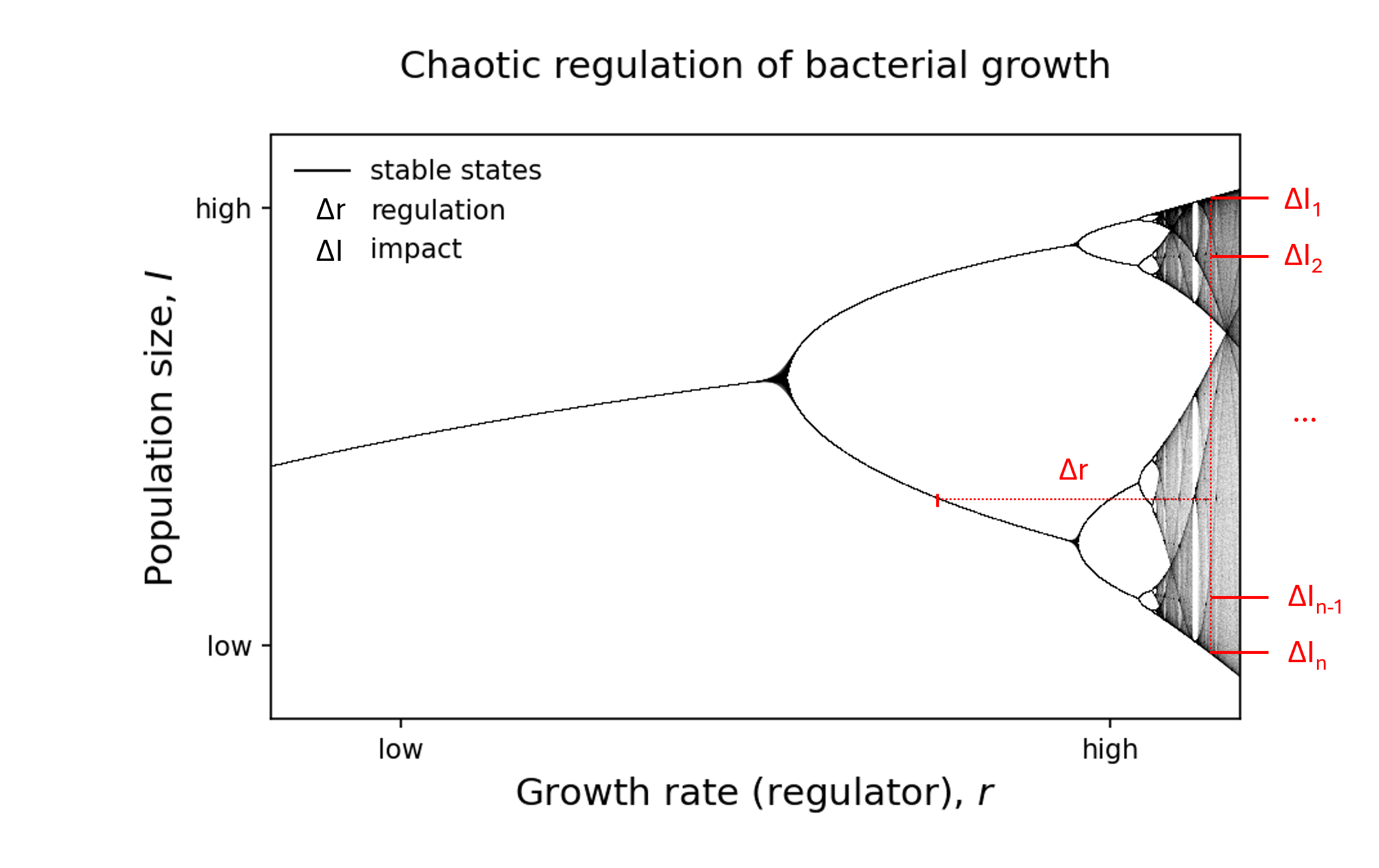

Chaotic regulation of bacterial growth

What if such bifurcations keep stacking up? In chaotic systems like stylized bacterial logistic growth, regulation can become nearly impossible. Here, a small change in the population growth (regulation, Δr) can lead to potentially infinitely many different future population sizes (impact, ΔI1, ΔI2, ..., ΔIn), making long-term prediction impossible. Regulating the system into this chaotic domain, actually means we are giving up more and more control over it.

Effective regulation demands an accurate model of the system’s behavior. Linear systems are easy to control, but nonlinear, hysteretic, probabilistic, or chaotic systems require careful understanding of their stability landscapes. Without this knowledge, regulation can be ineffective and costly.

Literature

[1] Roger C. Conant, W. Ross Ashby. Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system. Link.

[2] Hiroki Sayama. Introduction to the modeling and analysis of complex systems. Link.

Institute of

Environmental Systems Sciences

Merangasse 18,

8010 Graz

Environmental Systems Sciences

Merangasse 18,

8010 Graz

daniel.reisinger@uni-graz.at